Note from the Author:

This letter was initially written to Jill, the mother of my son Ben, in response to his ADHD diagnosis and the preparation for our first IEP (Individualized Education Program) meeting. It reflects my concerns and objections regarding the diagnosis and the proposed educational accommodations. The original tone and urgency of the letter have been preserved to maintain authenticity. However, I have refined the content for clarity and coherence to share my thoughts with a broader audience.

Here is the circular logic: How do we know Ben has ADHD? Because he exhibits certain symptoms. Why is he exhibiting these symptoms? Because he has ADHD.

Specifically, to meet DSM-V criteria for ADHD in childhood, a child must have at least 6 responses of “Often” or “Very Often” to either the nine inattentive items or the nine hyperactive/impulsive items. This is determined by a survey. The survey questions are so broad and transparently obvious that it’s easy to answer according to one’s preconceived conclusion. If you think you or your kid has ADHD, you know what answers to give. ADHD by definition is nothing more than a set of subjectively determined symptoms that may or may not be related to an underlying cause, an arbitrarily specific number of checkboxes ticked. That’s it. That’s what it is. There is no evidence or even a consensus theory for an underlying cause or etiology.

I’ve heard of a thing called ADHD that might explain away problematic behaviors in my child. I wonder if he “has it.” I’ll go to a credentialed doctor to have him diagnosed professionally.

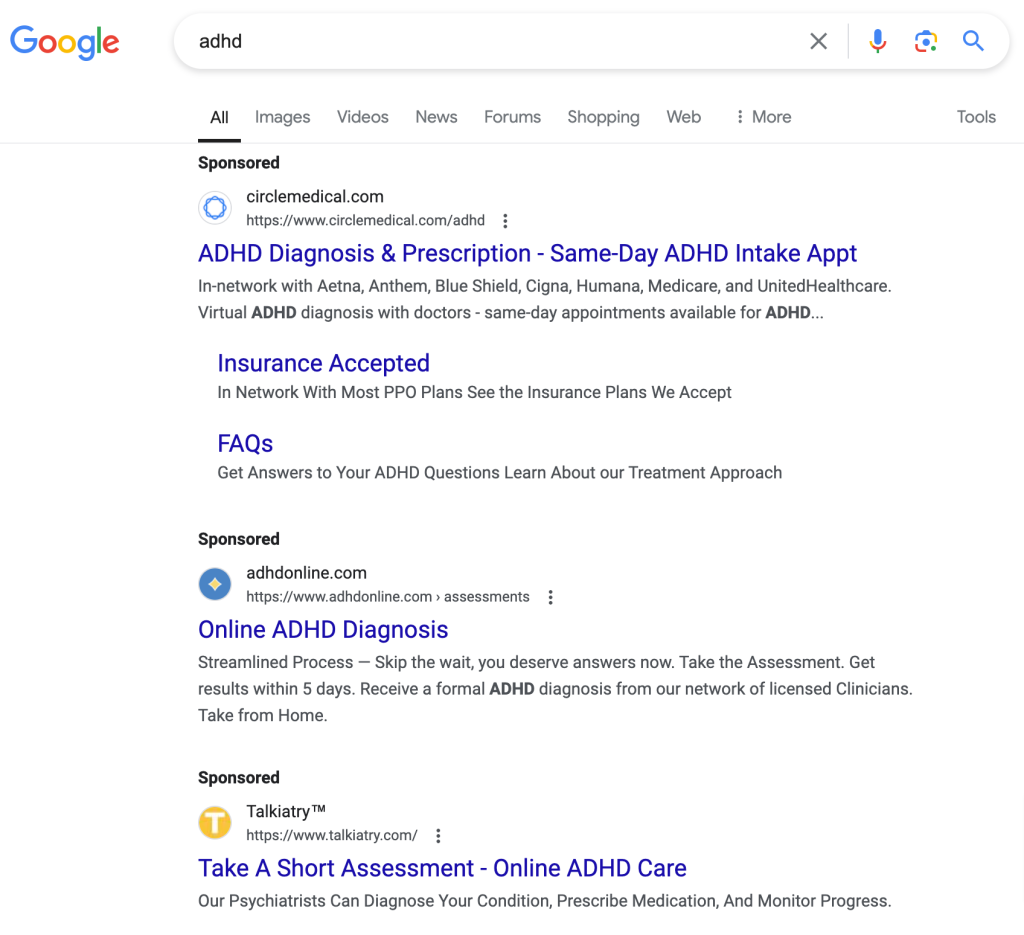

The doctor then asks transparently obvious questions that validate this preexisting interpretation of the behavior. The incentives for all parties align toward a diagnosis of the condition. Parents breathe a sigh of relief that it’s not their specific parenting style that accounts for particular maladaptive behaviors—it’s just an illness that happened to befall us. Maybe he was born with it? The doctor can prescribe medication or otherwise feel gratified that he’s identified the problem with his official label. Psychiatric diagnosis is closer to cold reading or astrology than it is to biology. Try googling ADHD and all the top results are along the lines of “1-minute diagnosis! No appointment necessary!” Seems legit.

Ah, but maybe this confluence of behaviors really does point to some underlying biological, neurochemical imbalance, or deficit? We don’t have the data, neuroscience, or genetic science to point to a cause just yet (though we’ve spent decades and billions of dollars directly pursuing a sound foundation for psychiatry without a shred of progress), but surely we will someday, right? Psychiatric diagnoses, as currently defined in the DSM, are categorically different because they are merely descriptive, never explanatory. It’s not just that we don’t know their causes yet; it’s that DSM diagnoses cannot speak to causes, now or ever. It is not designed to address causes, only to describe effects. The checkboxes of ADHD, in particular, are so varied that it is impossibly unlikely there would be a single corresponding biological factor like a gene.

Without a biological foundation, there’s no basis to assume that the varied “symptoms” are the result of some unified underlying condition. “Symptoms” of what? In other words, there’s little justification to call it a condition at all. What utility does the label ADHD serve beyond a DSM code for pharmaceutical and insurance companies (and protocols for state funded special needs programs)?

Valid illnesses and disorders don’t have this circular reasoning problem. For example, strep throat, like ADHD, has sizeable list of symptoms: throat pain that usually comes on quickly, painful swallowing, red and swollen tonsils, etc. However, these symptoms do not define strep throat. There are plenty of illnesses with similar symptoms. Strep throat is defined by a bacterial infection from Streptococcus. The symptoms point to an underlying etiology. A medical professional can test for strep throat using a rapid strep test or a throat culture. These tests are incredibly reliable. This is proper medical science at work. Psychiatry smuggles in credibility it does not deserve by sharing a vocabulary with proper medicine using words like mental health, mental illness, and so on. Behavior cannot be ill. To call behavior healthy or unhealthy is a bad metaphor that leads to confusion.

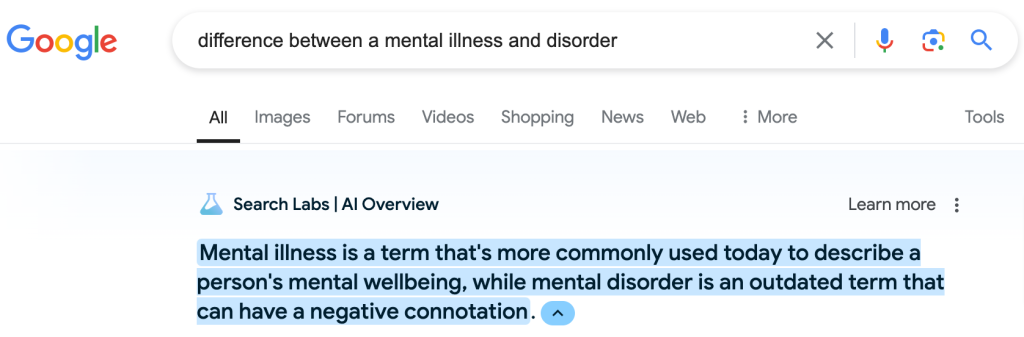

I was just about to give the devil his due and try to unpack ADHD as a “disorder” rather than an “illness.” ADHD as disorder makes a bit more sense and is less offensive to me logically, but I was surprised to find that mental disorder is out of vogue, now carrying negative connotations.

Some might argue that psychiatry is more like engineering than a hard science. There’s a problem or set of problems, and we can engineer a solution without a deep understanding of the underlying causes. However, ADHD is so broad and ill-defined that it cannot be treated as a problem to be solved as a whole. Each checkbox symptom could be treated as its own contextually maladaptive behavior. At best, you can say, “in such and such a setting, this tendency is inappropriate or maladaptive.” To lump them together accomplishes nothing without an etiology and a corresponding treatment for the underlying cause. The classification is positively harmful as it only adds confusion and imprecision. For example, checkbox 15 in the hyperactive symptoms section is “talks excessively.” (What an absurdly sloppy classification. What is excessive? In what context?) Checkbox 7 under inattentive symptoms is, “loses things necessary for tasks or activities (e.g., school materials, pencils, books, tools, wallets, keys, paperwork, eyeglasses, mobile telephones).” I can imagine solutions and behavioral strategies to practice for each separately but cannot conceive of anything that could possibly address those as a single entity called ADHD. Add in four more vaguely associated checkbox behaviors, and the fuzziness multiplies. No, man, ADHD is like a constellation of symptoms. You have to use your imagination! Do you see it? Try squinting! Totally looks like a bull. Yeah, now I see…looks like bull to me too.

The IEP

So ADHD is nonsense but what about the IEP, or individualized education program? ADHD is a useless distinction without a biological foundation that does nothing but create confusion from logical category errors. Even as a mere label for undesired behaviors, it adds nothing but imprecision. Given that ADHD is the sole basis and justification for our IEP, and that ADHD lacks justification, there is no justification for an IEP. Ergo, we don’t need an IEP.

If we don’t need it, should we still want it? It seems many parents go out of their way for these special accommodations. There are a plethora of YouTube videos and online resources about IEPs. The videos often depict a scenario of parents vs. the state, teaching parents how to understand their rights, get what they’re entitled to, and otherwise milk the system for all it’s worth. Surely, individualized special education is a good thing whether or not ADHD is a valid category, right? I don’t think that’s necessarily the case.

Vague problems get vague solutions. The IEP is as imprecise a solution as ADHD is a category of problem. The name would suggest otherwise, given that it’s supposed to be individualized. However, this “team” doesn’t know Ben as an individual. They know his “diagnosis.” Their computer spits out state-approved recommendations for that classification. Noble visions of enriching the youth aside, their motives also include getting through the workday and ensuring state compliance.

Be that as it may, there are actual problems that need solutions. If we’re going to do something, we should agree on the problem being solved and the goals we’re aiming for. The only problem I’ll fully acknowledge is that Ben needs to improve his reading ability. You’ll insist he needs help with his “executive functioning” as well. I agree that Ben, like most, could benefit from more self-regulation and organization. So, we want to improve Ben’s reading, his focus, his ability to learn independently, follow instructions, self-regulate, and organize. Let’s see how the IEP will help us achieve these aims, taking each proposed accommodation one at at time.

The recommended accommodations fall into three categories:

- Lowering expectations; allowing the team to serve as his “executive function”

- Not individualized or exceptional; a vague guideline that would benefit anyone and not Ben particularly

- Circular logic where the remedy is identical to the supposed problem

- Give adequate amount of time to respond: Lowering expectations

- Seating near teacher to increase focus: Not individualized.

- But yes, let’s do this. Simple, no IEP necessary.

- Reduce/minimize distractions in the environment: Not individualized

- What distractions exist in the environment that would uniquely affect Ben and not all other kids?

- Is a fidget not a distraction?

- Is leaving the class periodically not a distraction to Ben and others?

- Is it possible to focus on the lesson while pacing in the “movement corner”?

- Provide consistent structure: Not individualized

- This seems like a sensible standard for all children.

- Allow freedom to move about, stand, pace if needed: Circular logic

- Something is dreadfully wrong when the diagnosis, the symptoms of that diagnosis, and the solution to that diagnosis are identical.

- Multimodal instruction: Not individualized

- Buzzword for learning style. There is little to no evidence that anyone has a particular learning style. Preferences become self fulfilling. Everyone benefits from a “multi modal” approach, reading and listening at the same time, for example. This is where I anticipate Ben will see the special ed teacher instead of Mrs Hatlen. Hatlen was said to specialize in reading strategy (sounds great to me) whereas this woman said she specialized in the different ways kids learn. In other words, she specializes in bullshit.

- Break lessons or directions into smaller units: Not individualized

- If this is taught as a general strategy—teaching Ben to break down larger problems into smaller chunks—I support it. Again, it seems like a strategy that would benefit everyone and not particularly Ben. If it is an accommodation done for him, it is yet another bar lowered.

- Use organizational strategies: Not individualized

- Vague. What strategies? Organization is something everyone should strive toward. Again, what about this is individualized about Ben?

- Pre-reading questions to focus attention on essential information: Not individualized

- Pre-reading is supposed to help comprehension. The evaluations seemed to suggest Ben didn’t struggle with comprehension as much as decoding. What does this look like individualized for Ben? Is it not a basic strategy they’ve already learned? When/where/how does Ben learn pre-reading strategies? Again, more Mrs Hatlan and reading training if even necessary.

- Audiobooks: Lowering expectations

- If the problem we’re solving is reading, audiobooks simply dodge the problem altogether. Are we talking about reading along with an audiobook? When/where/how?

- Allow for extended time (when/how much): Lowering expectations

- lowering the bar. Note the ‘(when/how much)’ in parentheses which reveals the copy/paste auto generated nature of this ‘individualized’ plan. It’s like when actors accidentally read stage directions…or presidents say “pause”.

- Create timelines for lengthy assignments: Lowering expectations

- Ben should do this on his own, if necessary to complete the assignment. If the accommodation is for a teacher to do this then no. Assuming he’s incapable of this, isn’t solving a problem.

- Segment like information on tests: Lowering expectations

- Again, lowering the bar does nothing but give the illusion of progress.

- Supposed problem: Ben lacks executive functioning

- Proposed solution: Have a team act as his executive function

- Again, lowering the bar does nothing but give the illusion of progress.

- Tests read aloud: Lowering expectations

- Which tests? This will help test scores but how will they help Ben? Do MAP scores at this stage have real world consequences aside from this ordeal? Better get those MAP scores up so Ben doesn’t end up special needs?

- Provide a word bank: Lowering expectations

- Maybe they should just hire a specialist to softly whisper the answers to him?

Do we want a team to become Ben’s executive functioning? Do we want to enable dependence on the special needs team? How does this foster independence? The team seemed rather large. How close of a relationship could each of these people possibly create with Ben? How will interrupting general classwork help him catch up with the class? How will he not fall further behind when he’s missing instruction?

No doubt you’re assuming that the “stigma” around special education is what is motivating my aversion to this. First, unless you deal with the logic of the actual preceding arguments, my motivations are irrelevant. However, for the sake of argument, I’ll make it clear that I am, in fact, worried about the stigma around special education. Further, I’m not allergic to the notion of discrimination based on stigma or stereotype anyways. Definitionally, stigma is when someone views you in a negative way because you have a distinguishing characteristic or personal trait that’s thought to be, or actually is, a disadvantage (a negative stereotype). There’s a reality to the stigma. No amount of feminized, insincerely polite, politically correct bullshit will prevent people from interpreting Ben as special needs. I was reassured by this team of well meaning women that we’ve all moved beyond this social stigma but ultimately their argument seemed pretty retarded/moronic/idiotic/special needs to me. Please forgive my use of the “r-word” but I’m jumping off the euphemism treadmill. The stigma is not going away. Ben will eventually perceive himself as having special needs and he’ll eventually learn that special means something different in this context. This can do nothing but harm his assessment of his potential. Worse, he might become one of those irritating people that habitually uses a convenient label to excuse and avoid working on their shortcomings—the kind of person that lists their disabilities in their twitter bio.

I wrote most of that June 2, 2022. I think I knew at the time that it would be in vain and I really just wanted to officially document my objection. Shortly after we had our zoom meeting with the team to discuss Ben’s IEP. It was as robotic and bureaucratic as I expected. It was a little awkward when I started voicing my objections. It seemed as though the team had never experienced anyone who didn’t want an IEP. They were just going through the motions. It seemed that the collaboration and feedback from the parents as “partners” in this was a mere formality.

You see that I spent a lot of words trying to elaborate thoughts to Jill on why ADHD isn’t a valid or useful category, and how psychiatry is essentially pseudoscience. That’s a hard thing to summarize in a zoom meeting to people whose entire lives and livelihoods rest on the flimsy foundation of psychiatry. I had a few reasons for objecting. First, I objected because I didn’t want to participate in this lie. Second, I certainly didn’t want him to end up drugged on Adderall either. Have you ever done Adderall? It’s great. I’ve pulled incredibly productive all nighters coding, climbed 600+ flights on the stairmaster, and more. Everyone performs better on meth. It’s just not something you want to make a daily habit of and become dependent upon. However, my biggest concern, the primary reason I objected, was that I didn’t want Ben to be ostracized with a diminished sense of his potential. I didn’t want him to categorize himself into an invalid category like ADHD nor a category like special needs. I didn’t want him to think he was dumb. I should have leaned into this harder rather than regurgitating Szasz. I failed to protect my boy.

Were my fears realized? Of course. One night at dinner he called himself dumb. He called himself dumb two years in after entirely closing the gap in his reading ability with his peers. (A gap that was no doubt the result of some benign combination of being taught to read during the absurdity of 2020 and simply being a boy, rather than ADHD). Other kids called him dumb because they noticed some kids leave for “group” while others do not, and they counted Ben among them. Kids figure these things out quite easily. My son isn’t the victim of “bullying” either. He often plays with some of these same kids now. Other random 10-year-old boys aren’t the villains here. Occasionally, they find themselves in situations where they’re talking shit to each other as boys do, and sometimes it escalates a bit too far. Kids explore the boundaries of how far you can and should push each other physically and emotionally—normal stuff that is never going to go away. Some of them might actually be deviant, cruel monsters beyond repair—I’m not sure. That’s beside the point. The point is that because of this culture-wide confusion around ADHD, mental health, and psychiatry, my son’s feelings were hurt. I saw it coming and didn’t do enough to stop it.

Thankfully, Jill heard him say it too. She conceded that maybe this wasn’t the best approach to help Ben. We had our annual meeting to discuss the IEP and removed him, revoking the plan. While doing so, they pushed for a 504 plan. I suspect their funding is based on the number of kids in these kinds of programs, but I haven’t looked into it deeply. I’d put money on it, though.

When I told Ben that he wouldn’t need to go to group anymore, I did my best to frame it as a graduation of sorts, to punctuate it as a challenge that he surmounted, a level he had passed. I hope that it was enough for him to no longer self-define as dumb.

I’d love my son even if he were dumb, obviously. If Ben actually was dumb, and the other boys noticed, called him dumb, and hurt his feelings, this would be an entirely different train of thought. Being smart isn’t the only thing that makes someone valuable, worthy of respect and dignity. The annoying thing is that he’s not actually dumb and this could have been avoided. He’s a very clever and curious boy. He excels at math. I recently taught him Minuet in G on piano. That takes an awful lot of focus and directed attention for a 10 year old. It’s a miracle that he managed it without Pervitin.

Leave a Reply